Architectural evidence of success

Exploring William Orpen's Studio with Louise Campbell

This past autumn, my book 'Studio Lives: architect, art and artist in 20th-century Britain' was published by Lund Humphries (available here). The book discusses studios and studio-houses as places designed around the needs and tastes of the artists who used them. Studio architecture is essentially a hybrid, producing spaces which are simultaneously private and public. Not only does it create customised workspaces, but it also provides a stage for the occupant and a tangible demonstration of their success.

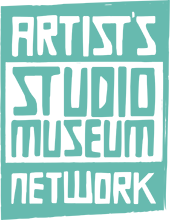

Nowhere is this more evident than in the studio of Sir William Orpen, whose London studio was meticulously re-fashioned to facilitate his career as a society portraitist. Doubled in size in 1929-30, it provided a comfortable and elegant venue for his sitters and a setting for their portraits. The studio is now used by the Royal Academician Ken Howard.

The studio plays a central role in the exhibition William Orpen: Method and Mastery at Watts Gallery - Artists' Village until the 23rd of February, book tickets here. Below is an abridged version of the chapter I contributed to the exhibition publication about Orpen's studio. The full book is available to purchase here.

William Orpen's studio was the hub of a phenomenally successful practice as portrait-painter. While other artists struggled to sell their work in the difficult conditions of the inter-war art market, Orpen prospered. The studio - remodelled in 1929-30 to his requirements - provides insight into his working methods, his taste and that of his clients.

After Orpen married, he used a studio in his Chelsea home. With the birth of his second child in 1906, Orpen - needing more space and peace - began to work elsewhere. The studio which he found in South Bolton Gardens was one of a row of speculatively-built studio-houses designed by the Arts and Crafts architect Walter Cave. Built in 1904, they had steeply gabled, slate-hung roofs, roughcast walls and small-paned windows. Each contained living accommodation on the ground floor, service rooms in the basement, and a tall, north-facing first-floor studio.

-

'Orpen's growing reputation encouraged him to think in grander terms than this simple studio'

-

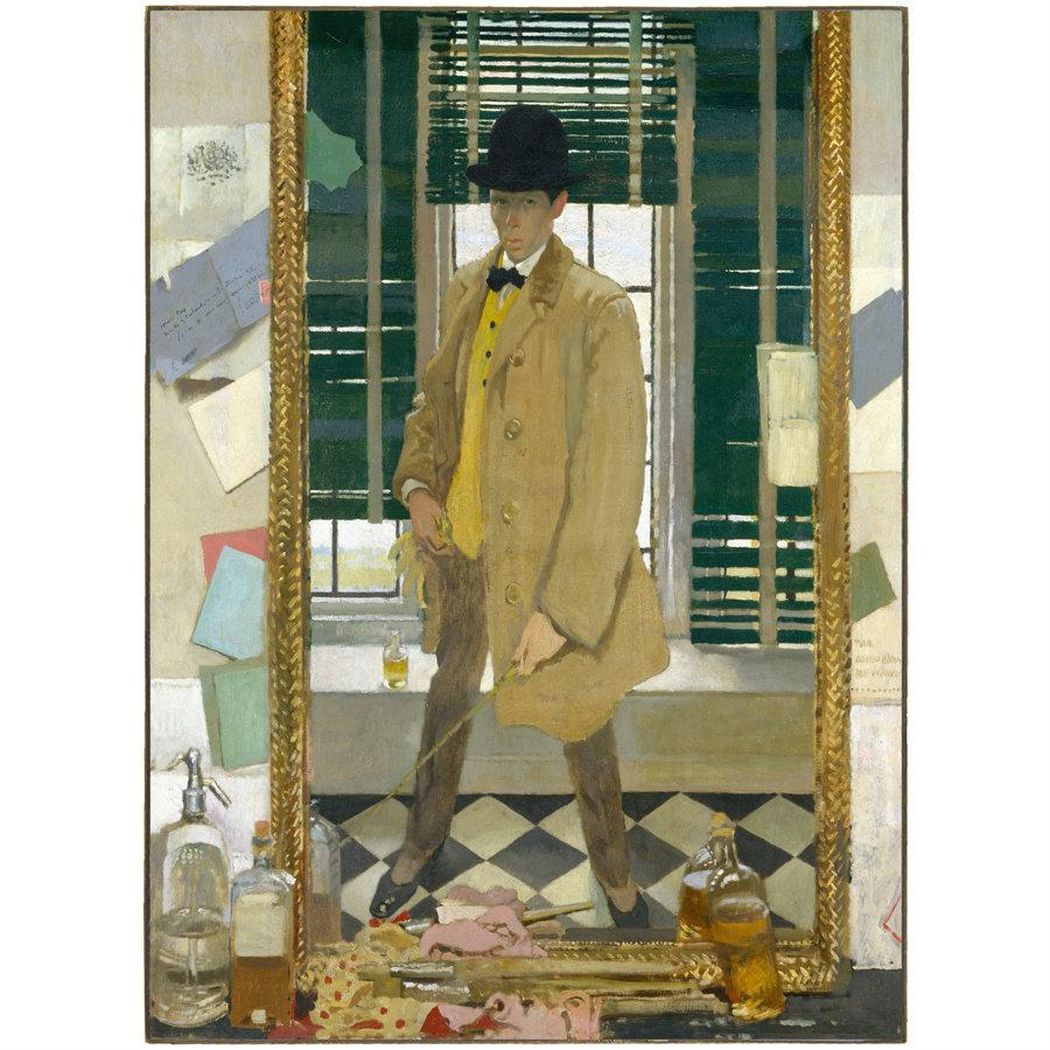

Orpen initially shared the building with Hugh Lane, the art dealer. When Lane moved out, Orpen took over the whole house. The studio and the sunny south-facing rooms behind it provided the setting for a series of paintings of himself and his models. They show the studio as an attractive room, with a black and white tiled floor, a plain mantelpiece and light filtered through green slatted blinds. But Orpen's growing reputation encouraged him to think in grander terms than this simple studio.

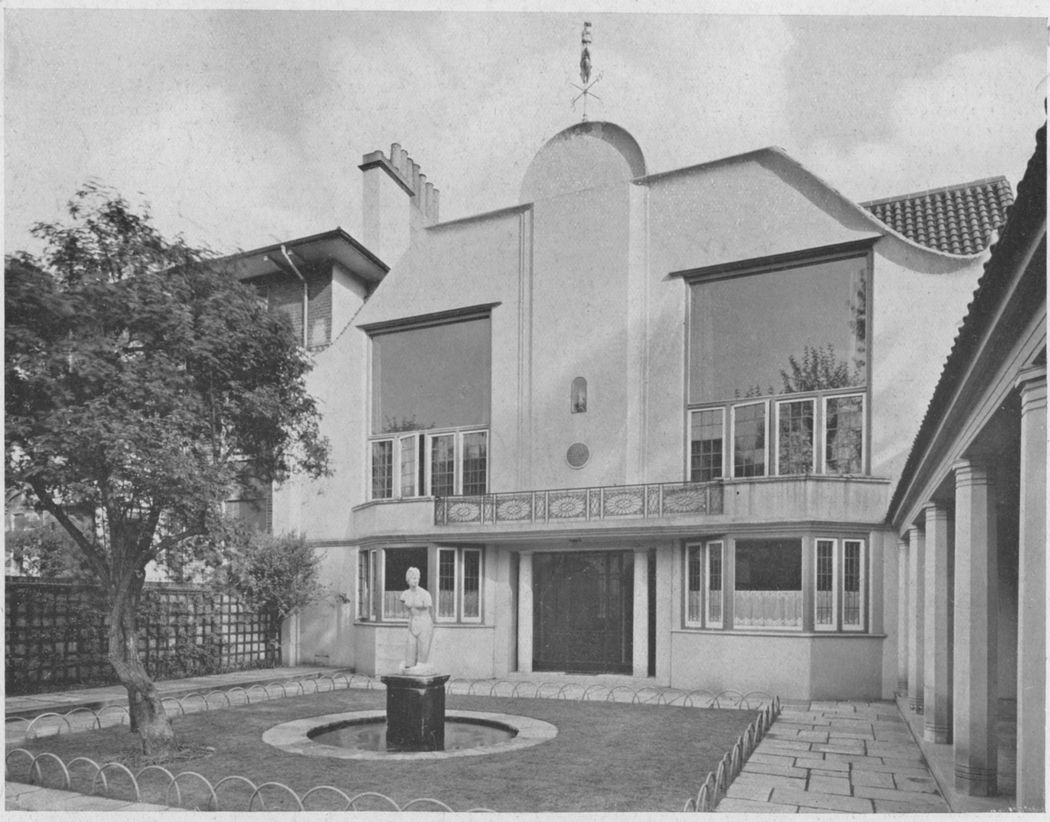

Orpen's studio book reveals a steady increase in his income from painting, with the proportion derived from portraits increasing sharply after 1918. In 1929, Orpen acquired the lease on the next door property, and asked his friend the architect J. Duncan Tate to merge the two houses. The façade was unified by a pediment topped by a weathervane and a columned entrance. Orpen's sitters were routed through a loggia which provided covered access between the street and the house, which they entered via a dedicated door. They were received in a pleasant ante-room before proceeding upstairs to the new double studio and adjacent dressing-room.

Orpen's requirements for light changed a great deal over the course of his career. In his early portraits, Orpen experimented with subtle variations of tone. After 1919, he favoured strongly modelled, clearly silhouetted figures. According to his biographers, 'Orpen arranged the light in his studio so as to strike the sitter from both sides (though not with equal strength), thus eliminating all heavy shadows.' The enlarged studio of 1929-30 helped him to achieve these effects.

-

'Orpen had strong views on interior decoration and an enduring love of the 18th century'

-

Huge sheets of glass were inserted in the upper part of the studio windows. Natural light was enhanced and supplemented with mirrors, chandeliers, wall-lights and two huge witches' balls suspended from the ceiling, which provided interesting reflections. The existing fireplaces and tiled hearths were retained, but the space of the two studios was unified by a new parquet floor and pale yellow walls. The wall between Orpen's studio and that of the house next door was removed and replaced with curtains and a wooden roller shutter, allowing the space to be subdivided. Orpen could paint his sitter while his assistant prepared canvases and palettes in the other half of the studio, thus speeding up his rate of production.

Orpen had strong views on interior decoration and an enduring love of the 18th century. The remodelled studio conveys this taste, pioneered by Orpen and other artists in the early 1900s. During the 1920s, with Victorian and Edwardian architecture out of fashion, the taste for the Regency became more widespread. The spacious elegance of Orpen's new studio was enhanced with Georgian furniture including Sheraton chairs, sturdy oak carvers and a splendid sitter's chair. It was a setting in which his clients could feel at home.

1929 was Orpen's most financially successful year, in which he earned an astronomical £54,729, most of it from portraits. The remodelled studio - the crucible for his practice – provided tangible architectural evidence of his success. A well-illustrated article about the studio published in Country Life in 1930 helped to confirm Orpen's status as England's premier portrait painter and contributed to the construction of his broader fame.

Louise Campbell

Louise Campbell has published widely on twentieth-century architecture. post-war public art and the design of artists' studios in France and Britain. Studio Lives: Architect, Art and Artist in 20th-Century Britain was published by Lund Humphries in 2019 and is available to purchase here.